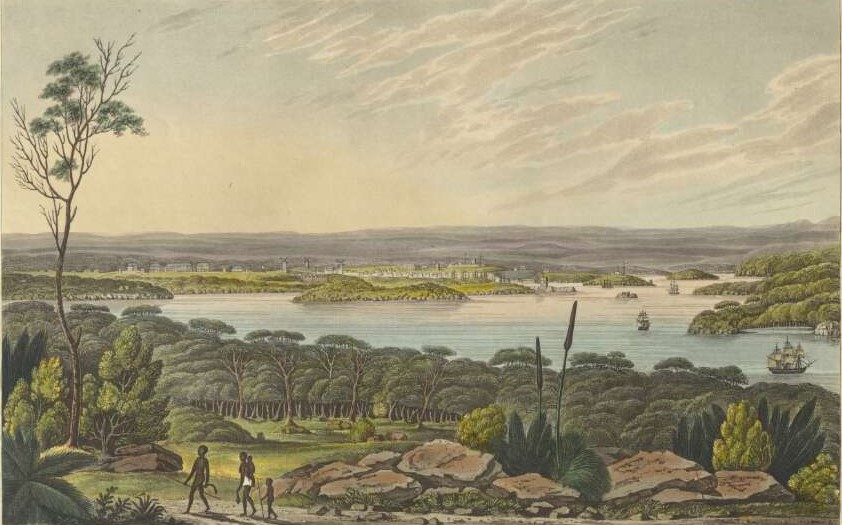

'Distant view of Sydney from the Light House at South Head, New South Wales', 1825

By Joseph Lycett, Published by J Souter, 1 April 1825, National Library of Australia, [PIC Volume 68 #U451 NK2707/4]

The views from the heights of the town are bold, varied and beautiful. The strange irregular appearance of the town itself, the numerous coves and islets both above and below it, the towering forests and projecting rocks, combined with the infinite diversity of hill and dale on each side of the harbour, form altogether a coup d’œil [glimpse or glance], of which it may be safely asserted that few towns can boast a parallel.1

~ William C Wentworth, 1819

William Charles Wentworth’s view from ’the hills on the south head road’ around today’s Darlinghurst conveys an idyllic picture of the town of Sydney in 1819. It was one echoed by many early colonial illustrations and paintings produced between the 1790s and 1850s, challenging perceptions of “Botany Bay” as a convict town with a tainted past.2

In some of these works, the windmills which once stood on the high ridge of today’s Potts Point / Derrawunn and Darlinghurst can be seen, grinding flour for the colony. These landmarks offered newcomers from distant lands a first glimpse of the town, as they sailed through Sydney Heads and surveyed the coves along the harbour.

It wasn’t just the natural beauty that would have struck the viewer as they passed the south-eastern shores of the harbour. Along with windmills, the heights of Potts Point and Darlinghurst were adorned with a handful of stately villas, occupied by the town’s elite.

After rounding the sandstone outcrops and eastern arm of Farm Cove / Wahganmuggalee, the imposing castellated structure of Fort Macquarie guarded Bennelong Point / Dubbagullee, and the public buildings established during Lachlan Macquarie’s administration lined Macquarie Street. This was Sydney Cove / Warrane, a busy port town.

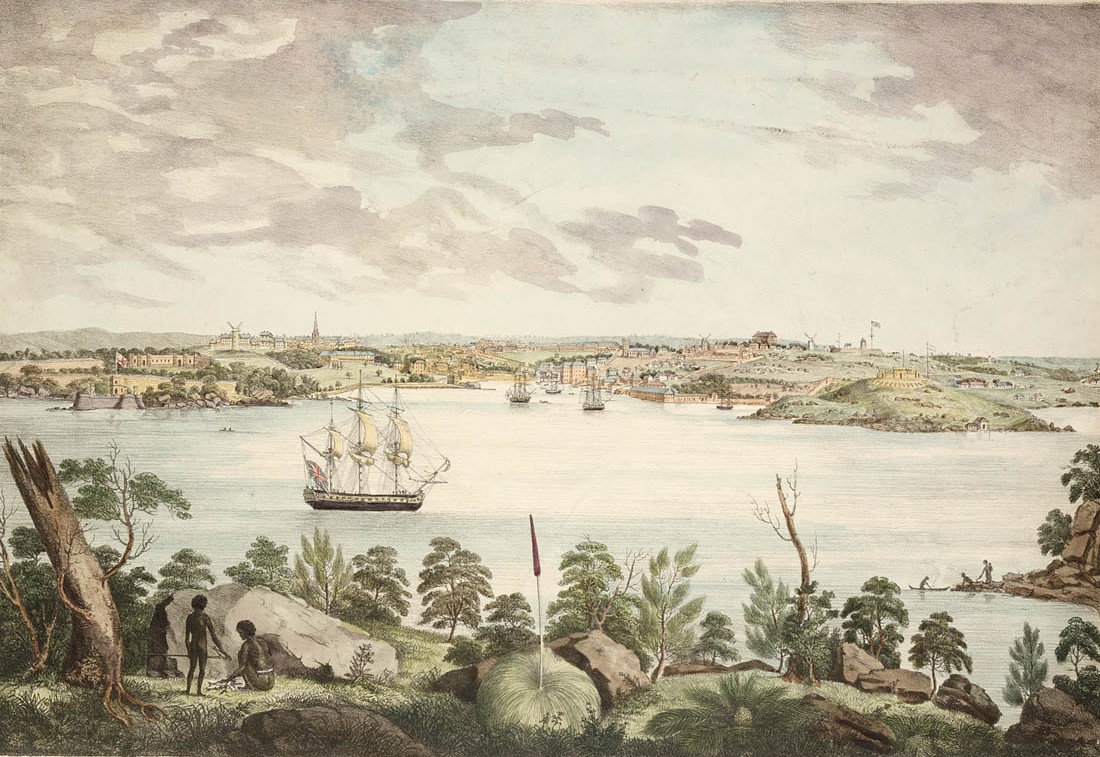

'North View of Sydney, New South Wales', 1822

By Joseph Lycett, 1822, State Library of NSW, DG V1/11

'City and harbour of Sydney, NSW, from the height above Vaucluse', c1855

Based on an oil painting by George E Peacock, lithographed by C Risdon, published by Day and Son, London, 1 May 1861, State Library of NSW, XV1/Har/1860-69/1

What these accounts and portrayals do not immediately show, however, is that they depict Aboriginal Country through a controlled, distinctly colonial lens. In these views, the sun is often shown setting or rising over a settlement established on British terms, characterised by order and a seemingly harmonious co-existence.

The structures of colonialism have been imposed on Aboriginal Country and using materials which had nurtured and sustained the Sydney clans for generations - sandstone quarried to make public buildings, shells crushed and burned to make lime for mortar, trees felled to make way for housing, rushes cut to make thatches for roofs, islands and ridges converted into military fortifications, and walking tracks turned into roadways.

Back to Wentworth’s forests, hills and dales, which he viewed from hills of Darlinghurst, and his words may be interpreted in other ways. Although much of the natural beauty of the area was still present at the time, Wentworth’s words hint at a broader message, one that foreshadows further incursions on Aboriginal Country and the transformation of a town into a city:

The neighbouring scenery is still more diversified and romantic….If you afterwards suddenly face westward, you see before you one vast forest, uninterrupted except by the cultivated openings which have been made by the axe on the summits of some of the loftiest hills….3

'Woolloomooloo Bay' 1843

By John Skinner Prout in Sydney Illustrated, 1843, State Library of NSW, [MRB/F981.1/P]

Read the next part of the story.

William C Wentworth, Statistical, Historical and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales and its Dependent Settlements in Van Diemen’s Land (London, UK: Printed for G and W B Whittaker, 1819), via Project Gutenberg. ↩︎

The term ‘Botany Bay’ was synonymous with New South Wales and often a derogatory moniker. Richard Neville, ‘A degree of neatness and regularity’ in 10 Works in Focus: Paintings from the Collection, State Library of NSW, 2018, Vol 1, 8, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/exhibitions/paintings-collection. ↩︎

Wentworth, Statistical, Historical and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales, Project Gutenberg. ↩︎